The "Architecture of Catastrophic Change"

(1990)

George Coates and his Multi-Media

Theater

by Steve Mobia

Writer's Note: It's ironic that there is so little about this pioneering theater group on the web since many Coates productions were directly commenting on this changing technology and its political/social effect. George Coates was, for two decades, the most celebrated director of experimental theater in San Francisco. Each show, despite occasional critical reservation, was given major attention by the city's newspapers. This you would never guess when researching Coates on the web today. As a fan of the work, this is my humble contribution to what is hoped to be taken up by others in documenting the innovations from this large group of collaborators. Because so many worked on these productions, I surely gloss over a few. My plan later is to list the original cast and crew for each production. The lack of footnotes in the article is because the writing came out of first hand conversations with George and others. As with everything else on the web, treat it with healthy skepticism. Please contact me if you worked on the shows or had seen many of them and have pertinent comments. (moviebeast@gmail.com)

The 1980s in San Francisco was fertile ground for a new type of theater, involving not only performance art but graphics, sculptural artists and musicians. Some astonishing productions were staged every year, each being a collaboration between the various disciplines. After each show had its run it dissolved into memory as only through those specific contributors could the production be realized. This was different than a standard play, which existed on paper and could be performed ad infinitum by any number of theater companies. These "multi-media" shows existed only as long as the collaborators worked together. One sensed a specialness to each production, knowing that it would most likely never be staged again.

Groups in the San Francisco Bay Area exemplifying this output included Nightletter Theatre (Sydney and Arthur Carson and their collaborators), Soon 3 (Alan Finneran), Antenna (Chris Hardman), Nightfire (Hardman's former collaborator and partner Laura Farabough) and George Coates Performance Works. There were many other more short lived groups as well for there was arts funding available at the time for this highly costly form of theater.

Nightletter Theater often used dream language

as a point of departure and employed the talents of sculptors and stage magicians

as well as filmmakers. The experience of their often spooky shows was highly

ambiguous as well as playful. Rooms, chairs and closets often held mysterious

creatures. Weird inventories of seemingly unrelated objects often brought up

potential meanings either through word play or visual association. Their later

productions were more like surrealist plays, with characters, costumes and

quasi-narrative situations.

Soon 3's work incorporated performance art into a sculptural landscape. Romantic and melodramatic contexts were distilled into symbolic gestures amid stylized props and film projections. Geometry, particularly triangles and colored fluids were systematically employed in slow ritualistic processes.

Antenna Theater invited the viewers inside the sculptural realm, using Walkman headsets to effectively make each person's experience more private as they wondered a "fun house-like" series of rooms and situations. Characters often wearing somewhat cubistic masks and costumes would interact with the mobile audience. Hardman and Farabough in their earlier company Snake Theater often used the world outside the playhouse to set the pieces (a gas station, a recycling center, a high school).

After splitting with Hardman, Laura Farabough took her Nightfire Theater into the outside world as well (one was staged in a swimming pool) but mostly stuck with standard performance venues. The stylized theatrical metaphors however remained.

Of these groups, George Coates Performance Works was the most technically elaborate and depended on the most collaborators.

Coates was an original member of an extreme group of Grotowski oriented actor/writers called the Blake Street Hawkeyes in Berkeley California (named for the location of their Blake Street theater). Started in the 1970s by friends Bob Ernst, John O'keefe, David Schein and later Cynthia Moore, their performances were sometimes like public exorcisms, with exaggerated characters, gestures and situations. This was quite the opposite of the style Coates would later adopt, involving abstract movements with little histrionic display. The familiar Hollywood actress, Whoopi Goldberg, performed regularly with the Hawkeyes (before she became well known). John O'keefe later was recognized and performed at other more well known venues such as Theater Artaud and Life On The Water at Fort Mason.

Coates also taught performance at a high school, where he and the kids would go downtown San Francisco to see how many people doing one thing would be needed to effect a change in the crowd. They would try to slow down a crowd or get them to listen intently to an unheard sound. Coates and some of the kids were also in William Farley's film "Citizen," where they were simply wandering through various environments while Bob Ernst, Whoopie Goldberg and others enacted a series of viginettes.

George Coates' technique for developing productions was an outgrowth of methods use by the Hawkeyes, although the results were less manic and visceral.

Basically, Coates would gather the best performers and stage technicians he could persuade to commit their full efforts to him.. They would meet pretty much every day of the week for months and generate material, experimenting and reworking images and ideas. Ultimately, Coates would pick and choose the things that struck his fancy and the show would gradually take shape. Even after opening a show, Coates would be changing elements, much to be frustration of some the stage crew and actors who needed to be adapt to whatever new notion Coates would scheme-up, often with little time. As the shows became more technically elaborate, this extended improv method of working became criticized as a costly indulgence by some. Still, during his most fruitful period in the 1980s and 90s, he managed to present an interesting production every year on a scale unseen before in San Francisco. Much credit for this went to the creativity (and patience) of his collaborators; including set designer Daniel Corr, music director Sue Bohlin, photographer/graphic designer Charles Rose, dramaturge Barbara Imhoff and many others.

After directing two solo shows in the late 1970s; one with mime Leonard Pitt ("2019 Blake") another with singer/actor John Duykers ("Duykers the 1st"), Coates scored an underground hit with "The Way of How" in 1981 using the actors from his solo projects, Pitt and Duykers, along with a new singer/performer Rinde Eckert. Composer and guitarist Paul Dresher provided original music. The show was a highly unusual mix of wordless opera, enigmatic business with a wheel chair and slide projections. Some of these elements would become fixtures in his future shows. The use of minimalist music, absurdist humor and surprising appearances of everyday items became constants as did the use of slide projections. The piece also had a transcendental quality that was hard to pin down. It's open ended structure left much to read in to. "The Way of How" had a long run for experimental theater and was staged in a variety of venues.

Dresher continued with Coates on two more music theater pieces, "are are" and "See Hear". These formed a curious trilogy and involved the same performers. "See Hear" also marked a collaboration with scenic designer Jerome Sirlin, whose inginuity with projections on ramps and flats became essential to the asthetic Coates would apply throughout his carreer. After "See Hear" concluded, Dresher and the performers had a split with Coates, seemingly about the use of narrative in the shows. Coates wanted to keep them non-narrative while Dresher and particularly Rinde Eckert wanted to write more story and character. After splitting from Coates, Dresher went on to compose and stage another trilogy with writer/performer Rinde Eckert and sometimes John Dykers. Unlike the Coates shows, the operatic settings actually used real words with subjects ranging from making of an American hit man (Slow Fire - 1988), to capitalism in the health industry (Power Failure - 1989), to the notion of the future as the last unexplored frontier (Pioneer - 1990).

_____________

Marc Ream became Coates' new composer in residence and their first collaboration "Rare Area" opened in 1986. Ream's music continued the minimalist methods of Dresher but with more of a pop flavor and more postmodern in the incorporation of diverse ethnic influences ranging from gospel to south african to eastern European. He continued to use operatic voices however and the first couple of shows had a similar effect as the Dresher productions with ambiguous wordless opera contrasted by humorous, sometimes satiric commentary. "Rare Area" featured performer Sean Kilcoyne playing a beer-swilling Vietnam vet making wry remarks as he watched slide shows, struggled with weather balloons, attempted an assassination of a royal couple and snapped flag poles. A mysterious silent woman, Hitomi Ikuma, haunted the proceedings. The subtext was vaguely political, evoking abstract anti-nationalist notions.

After a very successful appearance at UCLA and with "Rare Area" so well regarded in San Francisco, Coates took the gamble of a Los Angeles run in a major theater. The Doolittle Theater with 1,021 seats was a far cry from Theater Artaud in San Francisco where the show premiered. It was booked for one month. There was expectation that the show would gain traction if run long enough for word-of-mouth publicity. It was an amazing experience for all involved. Coates even invited the audiences to his hotel to party afterwards, allowing he and the crew to meet those as diverse as Ester Williams and Carlos Casteneda. However, the endeavor was a finacial bust with members of the company (such as Barbara Imhoff) having to put up their own money to get through the entire month.

"Actual Sho" was the most lengthy and elaborate of the wordless opera performances when it opened in 1987. The title was a homage to the "Actualist Conventions" that Coates was involved with back in the Hawkeye days along with the Japanese word "sho" meaning "to soar" or "fly." There were many singer/performers, several live musicians and Sean Kilcoyne reappeared as the "rational man."

It introduced a unique prop, a huge bowl or cone that acted both as a rotating platform and projection screen. The flat surface on the top could support actors and there were hatches that permitted actors to disappear within or emerge out of a projected environment. Patterns could also be projected on the curved sides for further hallucinatory effect. Because the cone was so large and heavy, it remained on stage throughout the performance and its theatrical possibilities were completely explored. As actors moved on the top, their weight could slant the surface back and forth. This inspiration occurred to Coates while watching Werner Herzog's "Aguirre the Wrath of God," where a raft covered in scampering monkeys and bobbing in a river suggested the possibilities of a tilting and moving surface. He got a jacuzzi company to build it out of fiberglass.

|

Cone stage (here upside down) being built for "Actual

Sho" |

"Actual Sho's" amorphous concept had something to do with an after-death experience. Kilcoyne refered to swallowing a chicken wishbone and possibly choking to death. His somewhat comedic spoken material contrasted with the wordless singers and chorus. Marc Ream's score combined minimalist electronic music with gospel-tinged passages. "Actual Sho," did well enough to take the huge production to Lincoln Center in New York and also to Yugoslavia and Poland where its depiction of people emerging from the underground (man hole covers and tunnels) had a symbolic resonance with the Solidarity movement. "Actual Sho" was the last Coates production to tour in Europe.

Steve Jobs hired Coates to create a short performance to introduce the NeXT Computer in 1988. George really hadn't explored the use of computers in his shows before and, in creating the performance (dubbed "Edifice NeXT" by Coates), he began to rub shoulders with people in the high tech multi-media industry. These sort of individuals became crucial collaborators, especially in the works produced during the 1990s. He also got to keep the 50 or so slide projectors used in "Edifice NeXT" (LCD projectors were many years away), and he used them to project textures not only on the stage but the interior of the theater itself.

|

Coates' next production for the general public was an unlikely collaboration with ACT -- a very traditional, very well-funded company of actors who regularly put on shows at a huge Union Square theater. "Right Mind," (1989) a music-theater extravaganza based on the works of Lewis Carroll, was scheduled to open the ACT season. Two years of research into the life and words of Charles Dodgson by collaborator Barbara Imhoff was transformed into a musical collage. It proved to be a challenging production, in large part because George's method of constantly changing, seemingly irrational improvisation over a period of months, clashed with the narrative script-based methods of the ACT actors and technicians. Though Coates used language extensively in "Right Mind," it was deliberately oblique and full of exuberant word play -- often taken verbatim from Dodgson's texts. To complicate matters further, there wasn't just one Lewis Carroll but five (each one representing a different aspect of Dodgson's "multiple personality"). To balance the equation, there were six little "Alices" (girls from the young performers branch of ACT), who goaded and chastised the various Lewis Carrolls and offered ironic commentary along the way.

Visually, Coates pulled out all the stops for this production. He used the rocking rotating cone stage from "Actual Sho," along with multiple film and slide projections by Charles Rose and John Scarpa. Marc Ream's pop-influenced music was generated "live" each night from Macintosh computers. Fire extinguishers were played as musical instruments along with Tyko drums. Two large weather balloons with an eye and mouth painted on them were floated outside the theater for publicity. The ACT subscribers had never witnessed such an odd production. Even so, perhaps out of shear novelty, the theater was packed during the first two weeks of its run, then disaster struck.

The 1989 Loma Preita earthquake hit the San Francisco area in the late afternoon of October 17th. Fortunately no one was inside the theater when the massive proscenium arch crumbled and lighting grid fell to the stage. "Right Mind" unexpectedly ended its run. Josh Chambers, a technician who worked with the company at the time, said that as a group GCPW never quite recovered from the loss of "Right Mind" and the potential revenue and status that the show may have generated.

Though there was much talk of remounting "Right Mind" in another venue, the only vestige of the ambitious production that saw the light of day was a small, highly revised reassembly of the material called "Right Mind is Nowhere," that was only performed for one weekend in Chico California. It reunited the six Alices, but the adult ACT actors had other commitments and did not reappear. The premise included the earthquake and an understudy (Robert Keefe, in the first of many Coates productions) pulled from the rubble of the theater. The understudy knew all the lines, but after being hit in the head by falling debris, he forgot the order of the lines. Thus, all the various personalities of Lewis Carroll were performed by Rob Keefe who would change his voice and tone, often several times during a scene. This admittedly schizo version was never seen by San Francisco audiences much to the disappointment of those who worked on it.

|

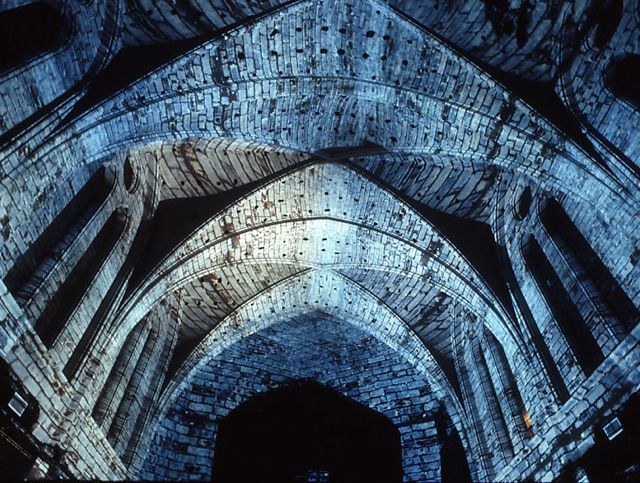

The vaulted 60' high cathedral ceiling

of the GCPW Theater with projected bricks from 16 carefully aligned

slide projectors |

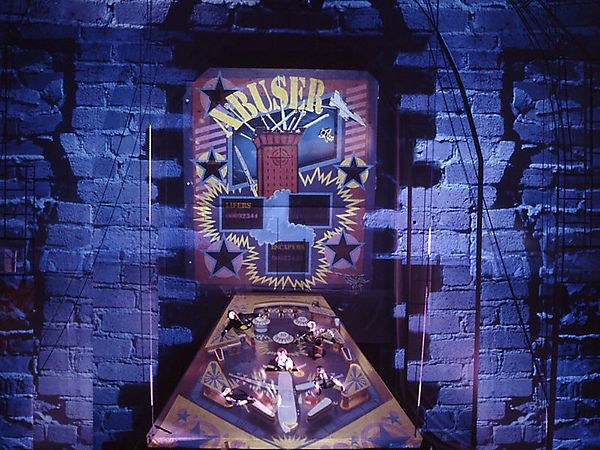

Again using the earthquake as inspiration, and with technical collaborator Daniel Corr, he revamped his large cathedral rehearsal hall into a 250 seat theater and produced for 1990, his longest running show: "The Architecture of Catastrophic Change." Even more elaborate than "Right Mind," "Catastrophic Change" utilized the 60 foot height of the vaulted church ceiling, with suspended platforms and a trapezoidal ramp that would raise and lower. The show's subject was nothing less than the future of humanity and the Earth, ranging from catastrophic personal and societal events, to ecology and the space program. It was a massive undertaking and combined improbable musical materials from the San Francisco Chamber Singers, the South African vocal group Zulu Spear and the Eastern European women's chorus Savina who all performed as singer/actors (notably the astonishing singer Susan Volkan who was to reappear in several later productions). Rob Keefe was cast as a product tester and placebo addict, who mysteriously survived every calamity he faced (even without the popular prosthetic body parts). One of Coates' more controversial ideas in this show drew upon the notion about how toxins produced in a mother's body, reject a baby so that it can be born into the outside world. His metaphor here was that pollution and abuse of the Earth was producing a toxic environment that would give birth to a new kind of human who was seen ascending to the stars at the end. The symbolic imagery in this production ranged far and wide and included much political commentary. For instance, at one point Rob's bed transformed into an enormous pinball machine titled "Abuser, " a war-themed game played by a young boy soprano who reappeared throughout. Company official's heads became bumpers on the machine and sang about the spilling of blood and oil (the show was premiered shortly before the first Iraq invasion of 1990)

Some who watched Coates' direction from "Right Mind" onward, were saddened that he appeared to leave behind the more open-ended wordless opera shows like "are are" or "Rare Area," with their spiritual, metaphysical effect and had gone into a more verbal, cerebral direction. The viewer couldn't just let the sensations wash over them as they could in, say "Actual Sho," but instead were subject to Coates' swarm of densely-packed ideas, wordplay and social satire. Jeffrey Hunt, who worked on the complex side projections in many of the early shows, later taught a college theater class where he attempted to get students to develop theater visually rather than always using text and narrative as a starting point. These techniques he learned to appreciate while working with Coates. One thing that could be said about the ambiguous spectacles of "Rare Area" and "Actual Sho," was that each element was no more important than the others. Charles Rose referred to it as a "phenomenon," a multi-sensory experience that could induce an altered state of consciousness. The extensive use of text in the works of the 1990s often felt at odds with the power of the images and music. Many critics however, said Coates was still too caught up in high tech effects and less in human drama.

Though the shows often did look very high tech, in fact that look was more the product of wizards such as Jerome Sirlin, Greg Allen, Joel Slayton and filmmaker John Scarpa and less the result of fancy machinery. In "The Architecture of Catastrophic Change," much of the projected imagery was from a battery of old fashioned slide projectors triggered by crude remote switches. If during a show, one of the projectors got a slide ahead of where it was supposed to be (or even worse if a slide got stuck), the technician had to climb up scaffolding to where the projector was attached and physically back the slide up. All this was about to change though with Coates' next production, "Invisible Site," a show that flaunted its high tech design.

Originally created to be premiered at the 1991 SIGGRAPH computer graphics trade show in Las Vegas, and later opening in San Francisco, "Invisible Site" went through several incarnations and months of improvised creation. Engineers from Silicon Graphics and other programmers worked on the startling visuals. A 50 percent perforated screen was set up in front of the stage. When images were projected on the screen and actors were lit behind the screen, the audience perceived the actors as being inside the projected "set." This illusion was greatly heightened by the use of 3D glasses. The result was essentially a highly refined version of the slatted scrims he used in previous shows but now he could incorporate 3D graphics and animation. In the version prepared for Las Vegas, the show directly drew from "tech talk" in the corporate world with Rob Keefe playing a computer game salesman who traps a gamer within his own game. The gamer just wants to "opt out" and get off every mailing and marketing list. The show was layered with satire that was best appreciated by those in the computer field. After the convention ended and Coates returned to San Francisco, he knew the general public would not understand much of the high tech lingo. Instead of dumbing down the corporate satire, he completely threw out the original script and put together something much more poetic.

Drawing from the life of poet Arthur Rimbaud and mixing in the plays "Medea" and "The Tempest," the San Francisco version of "Invisible Site" was the first stage production to explore "virtual reality" (a term that had just recently been introduced into popular culture). A woman and a man put on virtual reality helmets and entered another dimension where they could take on other identities. This pleasant fantasy was sabotaged by the anarchistic hacker Rimbaud who challenged the predictability of the virtual world and confronted the woman who had taken the role of Prospero from "The Tempest." The show explored the nature of being an exile and featured a brilliant centerpiece where homeless beings moved through the charred ruins of houses (3D photos of the recent firestorm in the Oakland hills).

Despite its audacious unconventional structure, "Invisible Site" was very favorably reviewed by many publications and enjoyed a long run. His subsequent productions never again achieved this unanimous praise.

"Desert Music," which was the first Coates production to use an existent musical score (by Steve Reich), took as it's subject not the context of the sung William Carlos Williams poems, but instead focused on airplane hijacker D.B. Cooper. Cooper hijacked a Boeing 727 aircraft in 1971 and parachuted from the plane with $200,000. He was never seen again, leading to much public speculation. In "Desert Music," after Cooper parachuted from the plane, he had a series of hallucinatory experiences involving his relationship to the almighty dollar and his eluding the authorities. These sequences could easily be compared to the after-death visions of "Actual Sho" with Cooper's soul in a kind of limbo. In a memorable theatrical gesture, Coates released from the ceiling of his theater 200 or so real dollar bills to shower down on the audience at every performance. The audience was encouraged to return the money when leaving the theater, though it was a choice made freely by each audience member. The production was quite extensive and utilized the vocal talents of the San Francisco Chamber Chorus, outfitted with penlight headgear and robes.

One of the problems when a company is known for visual spectacle, is the public expectation that each successive show had to top the last. Coates had been joking about doing a production with four people on a bare stage but added that everyone would hate it. Well, after "Desert Music," in 1993, he took a surprising turn and directed a pre-existing play "Waiting for Godot" by Samuel Beckett. Aside from a projected moon and some smoke effects, there were no other Coatesean illusions.. It was a powerful adaptation of the cellebrated absurdist play and though critically acclaimed, did not draw enough of a crowd to extend its run.

|

Tim Wiggins as Derek

Hornsby in "Box

Conspiracy" |

"Box Conspiracy" of 1993, was far more of a traditional narrative structure but was developed in the same improvisatory way as the other shows. It was almost as if Coates was showing his critics that standard narrative techniques could be utilized as much as the metaphoric stream of consciousness devices to create a production. What evolved in this case was a satiric jab at interactive television. The Hornsby family; an unemployed husband, his agoraphobic wife and daughter in desperate financial straits, decided to become a test family for a 5,000 channel television box. There's a specialized channel for everything, from beer to cooking to shows with titles like "My Favorite Mayhem." In exchange for the goods and services provided, the family lost its privacy to the wiles of Tom Testa, a corporate marketing agent who became their nemesis. The husband, Derek Hornsby, had developed the "Pocket Disorganizer," a device designed to scramble scheduling and planning so you'd meet unexpected people and go to unplanned places. After the tables a turned on Tom Testa during an interactive game show where the theater audience became the judge, the victorious Derek Hornsby applied his disorganization principle to subvert billboard and print advertising. "Box Conspiracy" was chosen for the renowned Spoletto Performing Arts Festival in Charleston South Carolina. Tim Wiggins, who starred in this show and two others, made these observations:

"Box Conspiracy" was created during the birth of the internet's transition to public domain, long before AOL, long before images and graphics, long before most people understood what a URL was (including me and most of the cast). George was working in a program (he may have created it) called SMARTS, for Science Meets the ARTs. He had an inside track with silicon valley engineers, executives, and funding. (Some of the visual artists and graphics designers who worked on the show were quickly snatched up by high-tech companies to create early visual web designs and interfaces.)

So while "Box" was ostensibly about interactive television, it was actually about the promises and pitfalls of the coming internet. (Derek's daughter in the story had an obsession with spiders, so there were plenty of "web" references and a song as well.) Aside from the 'point and click' purchasing offered by Tom Testa, all the Hornsby family's actions were monitored (it almost goes without saying how prescient this was). In the end, Derek's repeated ordering of triple-sausage pizza resulted in a massive increase in his health insurance premiums.

Next year's production "The Nowhere Band," had opened in Tokyo Japan and appeared as somewhat a pastiche of his past work. It was also the first theatrical production to utilize actors from other locations to perform via live web-streaming (using CU-SeeMe) . Their projections appeared on stage along with the physical actors at the theater. It was low resolution and step-framed, but it was live. The premise was that a little girl from the future (played by Coates' four-year-old daughter Gracie), was auditioning members of a pop band to help her find a magic bird. The Marc Ream music was recycled from previous shows but performed live by the band. This daring jumble of ideas and concepts concluded with Gracie dressed as a bird and suspended by balloons, floating out over the audience.

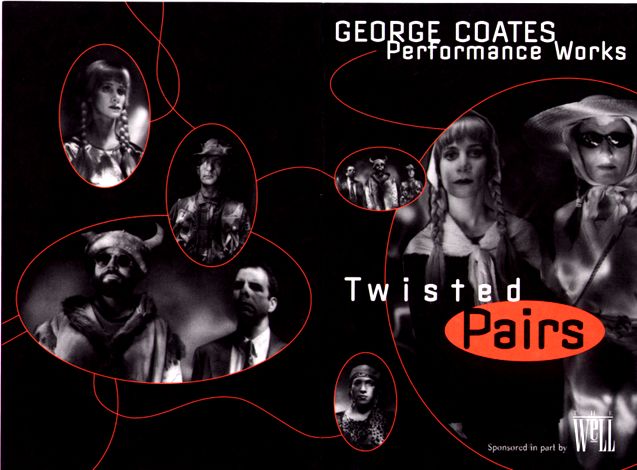

"Twisted Pairs" from 1996, found Coates diving headlong into the World Wide Web as subject. The effect was much like spending time web "surfing," as one topic linked often unpredictably to another in a string of tangents. The comedy was stuffed with ideas and wordplay, and depended on the audience being familiar with internet terminology. In 1996, many were online but just as many weren't, so reaction to the humor was spotty. As an aid, a glossary of internet terms was printed in the program. In this regard, the show was at least 2 years ahead of its time to work as a popular comedy.

|

Coates and company investigated Usenet groups and digital bulletin board discussions. The complex story for "Twisted Pairs" grew out of personality types discovered online. Susan Volkan played an Amish farmgirl who found a laptop in a crashed plane and later, through the help of subversive Flame Smith, became the revered Annette Diva, an internet celebrity and "fall guy" so that Flame could operate more secretly in her culture-jam attacks on the web. Sister Justice, a Jewish activist, led the Femfighters. Along with Derek 2.0 (Tim Wiggins reprised his Derek Hornsby roll from "Box Conspiracy"), they took over a news station from beer-guzzling Jack Troll to access satellite television so they could rearrange TelePrompTers for newscasters to read surreal text (an echo of the Disorganizer). They decided to set up a news station "Better Bad News," but the show ended right after the first broadcast. If that sounds convoluted, it was. Also somewhere in the mix was a search for the young Pachem Lama of Tibet and a Christian missionary with neferious plans. Though "Twisted Pairs" continued to utililize 3D glasses and projections, verbal exchange was emphasized over the music and visuals. This was the last production scored by Marc Ream.

Coates' earliest show as director from 1977 when his company was formed, was a solo effort with mime Leonard Pitt titled "2019 Blake," which was the address of the Berkeley theater that first staged it. Some in the audience at other venues however, thought the title was a refernce to mystic poet/painter William Blake. So in 1997, when it became time to celebrate the company's 20th year of existence, George made a variation on the old title and called it "20/20 Blake" (with 20 referring to 20 years and also the notion of "visual acquity" - 20/20 vision). It was a tribute to the inner world of William Blake. Collaborator John Rock made stereographic replicas of Blake's famous illustrations, and the actor/singers represented figures from Blake's personal mythology (the prophet Los, the feminine soul Thel, the rational materialist Urizen and Blake's wife Catherine who at times became the goddess Enitharmon as a glowing entity). The text and songs included Blake's poetry along with a story about Blake making his own death mask and the irksome Mr. Wedgewood who kept insisting Blake do commercial illustrations for selling his tea sets while calling Blake's visionary art "ugly." Urizen, as a bringer of pain and torment, punished the youthful physical passion of Los and Thiel in one of the few erotic scenes Coates ever staged. Though many of the props and effects had been used before (the expandable "scissor cage," the use of metal tape measures to create geometric forms), they had a more coherent relevance here and the show was strikingly poetic with an interesting eclectic live score by new composer Adali Alexander as well as Todd Rundgren. It was the last of the shows to use 3D glasses..

|

20/20 Blake |

The unlikely amalgam of the 1998 production "Wittgenstein on Mars," was inspired both by philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein and the recent Pathfinder Mars mission and grew out of improv sessions with German actor Walter Dickhaut and Punjabi actor Ravinder Gill. The subject of Coates' final biographical drama was surprising. Rimbaud, Dodgson and Blake found value in the illogical while Wittgenstein was searching the limits of logic through the use of logic, by questioning language. The show began with the reading of a headline about the possible discovery of bacterial life on Mars from fossils found in a meteorite in Antartica. These newly valuable Martian meteorites brought two research technicians to that frozen desert, expecting a new gold rush and thoughts of cashing in with karaoke and oxygen bars in the region. Alongside this story, was Wittgenstein taking on a sarcastic student to whom he espoused his philosophy in shouted rants. The music this time was not original, but piano pieces by classical composers Wittgenstein had known such as Brahms. Schubert and Ravel -- often accompanied by a live, singing painting. Dickhaut's portrayal of Wittgenstein was mostly angry and arrogant, making him a thorny protagonist and suggesting the inhospitable atmosphere of Mars. At intermission, the audience was invited to an "oxygen bar" in another room and treated to inhaling scented gas. Oxygen bars became a trend in San Francisco around that time.

|

| "Wittgenstein on Mars" 1998 |

Alongside the main productions, George also did shows for various computer companies and conferences such as the first version of "Invisible Site" for the SIGGRAPH convention in Las Vegas. There were also installations and gatherings in the theater, such as "Black Screen Cathedral" -- put together by Charles Rose and Marc Ream during the run of "The Architecture of Catastrophic Change," using music and projections not included in the main show. "Triangulated Nation," from 1999, was one of these installations, in collaboration with Lalo Cervantes from the San Francisco College of Arts and Crafts. 24 triangular plumb-bobs were suspended from the neo-gothic ceiling while a costumed chorus circulated to music by Adali Alexander. This became a part of "Blind Messengers," a Sesquicentennial show in Sacramento on one evening for an invitation-only crowd.

The final 3 productions staged at GCPW were quite a departure from the works that built Coates' reputation. In the late 1990s, funding for elaborate theater projects was drying up fast. Rising rents were forcing artists to move from the San Francisco Bay Area and many storefront theaters and rehearsal spaces closed. Rather than produce low budget versions of the multi-media dreamscapes he was known for, but still desiring to have a conceptual impact on the theater world, he hit upon a very different tactic.

After watching the 1996 film "I Shot Andy Warhol" by Mary Harron, George was haunted by the missing play that motivated radical feminist Valerie Solanas to shoot the pop-art master. "Where was the play?" he asked. The Solanas play "Up Your Ass," was thought to be lost amidst the clutter Warhol collected. Warhol is said to have thought Solanas' play so scandalous that she might have have been working with the police to set up an arrest and conveniently lost it. Another view was that Warhol simply had no interest in the play and truly lost it (the only copy). Solanas however, felt that Warhol and her publisher were plotting against her and planned to produce the play themselves, without regard to her input and not paying her. She showed up at Warhol's "Factory" and shot him 3 times. Warhol barely survived and slowly recovered after 2 months in the hospital, and Valerie -- diagnosed a paranoid schizophrenic -- got 3 years in prison and treatment before returning to a life of prostitution and drugs, holding out in a welfare hotel in San Francisco's "Tenderloin" neighborhood before dying of pneumonia in 1988, just up the street from what became Coates' McAllister street venue. Whatever remained of her later life writings is said to have been destroyed (burned) by her mother.

The storied but unknown play was discovered in a silver trunk among Warhol's possessions along with photographic lighting equipment and, in 1999, Coates discovered it at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburg. And so, in 2000, the 35 year old play was finally given its world premiere by, of all people, George Coates.

Because even the title was scandalous (and often abbreviated or censored from the later ads), Coates usual support from established art patrons in San Francisco was in question, let alone the impossibility of getting funded by the NEA. He decided to stage the Solanas play alongside a respected mainstream playwright's work (Arthur Miller) and both were presented concurrently on alternating nights and with the same cast of "drag kings" playing the men. Also the Miller play "The Archbishop's Ceiling," was concerned with censorship in the Soviet Union -- a wry commentary on censorship in public arts funding that plagued congressional debates, spearheaded by arch conservative Jesse Helms. George expected audiences to see both plays and to compare and contrast them.

The shows couldn't have been more different. "Archbishop's Ceiling" was sober, refined, restrained. The actors took their roles very seriously and the self-conscious paranoia made clear in the dialogue was effectively palpable. In contrast, "Up Your Ass," was an unhinged karaoke satire -- rife with profanity, scatology and, eventually, murder. Coates had been toying with karaoke since "Wittgenstein on Mars" (setting Wittgenstein philosophy to country and western), and in "Ass" it took over. The alley setting of the original play was conveniently changed to a karaoke bar.

Assistant director Eddie Falconer had introduced Coates to the world of "drag kings" (women who enjoy dressing as men), and it is from this subculture that Coates recruited his actors. As with the SCUM manifesto, Solanas' most famous work, much of the feminist commentary in the play is on the level of diatribe with obvious symbols (ie. women eating turds on stage as reference to how women have to "eat shit" on a daily basis). The value of the 1965 play is through its historic importance as the leading edge of the women's movement taken to extreme ends. Solanas was able to craft humorous satire about gender issues she cared deeply about and created such wild caricatures that they called for special treatment. Coates' decision to turn it into a musical (setting the text to pop music from the period that Solanas would've been hearing) proved an ingredient that invigorated the action. The play's acerbic satire was preserved, but the show never bogged down despite being two hours with intermission.

"Up Your Ass" proved to be the last critical and popular hit for George Coates, and even had a New York run. There was a cult following of repeat attendees that George fondly referred to as "Ass Heads." However, "The Archbishop's Ceiling," the somber play about government surveillance, was dismissed by critics as emotionally flat and concluded its run early.

Sara Moore, the actor who played Bongi Perez (a mouthpiece for Solanas) in "Up Your Ass," returned as lead in Coates' final theatrical production "The Crazy Wisdom Sho." Coates claimed the Wes "Skoop" Nisker book titled "Crazy Wisdom," kept falling from its bookshelf in his home and, in the spirit of the book itself, he took that event as significant and put together what originally was going to be a traveling show in the manner of wild west medicine shows. Eventually, what was staged had little from Nisker's writing, apart from the title, and was littered with paradoxical quips ("when laws are outlawed, only outlaws will obey the law"). Another notion was to present the show as a conference about appropriation and authenticity. For example: Instead of claiming that President George Bush "said" something in a speech, Coates felt it was more appropriate to state that Bush "read" (since speechwriters, more often than not, provide the words). To explore this concept further, Coates placed five teleprompters around his theater and made Sara a speech instructor with a multiple personality. An "empowered multiple," Sara embraced rather than medicated her tendency to become other entities and Coates gave her free reign to transform her behavior and voice. In addition, Coates invited internet surfers through his website to contribute their own "crazy wisdom" to be read off teleprompters by performers in the show. Nigerian actor and singer Babatunde Garaya, as well as Michaele De Cygne, rounded out the small cast. At one point, Sara became a scholar with slide show illustrations, discussing controversies around the authorship of Shakespeare's plays. George, convinced that Shakespeare was essentially illiterate and the 17th Earl of Oxford actually wrote the famous plays, at one time wanted to devote an entire show to this subject. In "Crazy Wisdom" it became a sober sidetrack into the nature of appropriation. Despite some manic physical humor and musical numbers (including a percussion trio on spouting fire extinguishers), "The Crazy Wisdom Sho" was, essentially, eccentric verbal hijinks with little visual impact. After its run, the theater went dark and has never re-opened.

|

Babatunde Garaya and Sara Moore in "The Crazy Wisdom Sho" |

The Hastings Law School that housed the Coates theater, claimed that Coates had violated the 20 year contract by not doing proposed improvements to the building. For instance, the cathedral initially had a suspended ceiling, concealing the upper part of the building during its use years earlier as a Vietnam War recruiting center. Coates took out the suspended ceiling but never fixed the holes in the arched plaster above or the exposed beams and supports along the walls. George actually liked the cathedral as a ruin and so never made repairs. Also, a side room with wooden walls was scratched up from its being used for prop storage. Since Hastings was a law school, it was deemed foolish to fight the eviction in court.

Though it seemed for awhile that George would secure another permanent home in another church, that deal fell through. Since 2001, there has not been another George Coates theater show either in San Francisco or elsewhere. The production office was shut down. "Seismic upgrades" was the public explanation for the theater closing.

So, what happened to George? Well, his obsession with teleprompers in "The Crazy Wisdom Sho" became a catalyst for a project that lasted for many years, longer than any previous Coates production. After making an arrangement to teach public speaking to a group enrolled in a Berkeley adult school, George set up a website and videotaped the results. Originally, the material to be spoken was to be contributed by people on the web, where one could pick the announcer to speak the submitted lines. This had a distinct connection with the original concept of "Twisted Pairs" and "The Crazy Wisdom Sho," where the lines the actors said were supposed to be created by web surfers. Coates used a fictional Berkeley coffee house "The Cafetorium" and had a panel behind a long table. There would be someone standing, announcing something into a microphone that the others would comment on. For a title, he used the name of a news station from his show "Twisted Pairs" and called it "Better Bad News." Since the first program had the effect of a surrealist game, "The Exquisite Corpse," the result was a string of non-sequiturs. Apparently, Coates wasn't satisfied with this and started writing the lines himself. The shows, lasting an average of 5 minutes, were either political or based on issues concerning the "blogosphere." As usual, the Coatesian cleverness and humor was very present, but gone was the imagery. The visual material rarely strayed from the seated panel, except when an appropriated scene from the internet was cut in.

Also, a tendency in many a Coates show with text was given full bloom here; conspiracy theories -- in this case regarding the 9/11 attacks among many others. Previous shows had delved briefly into conspiracy concepts -- as early as the Las Vegas version of Invisible Site, where one subplot involved fictitious children being used on milk cartons in order to scare parents into registering their kids with the government and joining the national ID card movement. In the case of Better Bad News, Coates believed the Bush administration or some group connected to them were responsible for the attack on both the World Trade Center and the Pentagon and he spent quite a few BBN entries on this subject. Other programs were prescient of revelations later made about NSA surveillance and the internet as a massive spying machine. Though there are some real satiric gems within the years he worked on the show, many of these "video blogs" (with deliberate choppy editing by Coates himself in his backyard studio) are curious mainly to contrast with his legacy of visionary theater. It's telling that Coates' name was nowhere to be seen on the Better Bad News website. The final shows in this series were completed in 2011.

Currently, George has been producing KPFA's "Twit Wit Radio" using many of the same performers as Better Bad News and plays as an audio version of the same kind of thing, so those fond of BBN should tune in for some political amusement.

In its heyday, the theater of George Coates

Performance Works was utterly unique and groundbreaking, both

in its exploration of technology and the scale of its productions. Many innovations

from Coates’ team

later made their way into the more publicized work of maverick director Robert

Wilson and turned up in operas by Philip Glass. Still, there was a West Coast

irreverence to the Coates productions that gave them a distinctive edge. Even

The Blue Man Group can be seen as foreshadowed by the early Coates/Dresher

performances like “The Way of How” in combining music, humor

and unexpected use of common objects along with a strong absurdist

sensibility. George was able to orchestrate collaborations between Silicon

Valley and a host of graphic artists and the result produced the most exciting,

creative and bizarre spectacles San Francisco had ever seen. His passion for

non-narrative image-based music theater infuriated some though his extended

improvisation methods generated rarified timely treasures that couldn’t

have been achieved any other way. It is hoped that this work be remembered

and documented for all the efforts by so many over the years.

|

The exterior of the George Coates Performance Works Theater on Mcallister street in San Francisco. Since Coates' eviction, the theater has gone unused.

|

| MUSIC EXAMPLE from "The Architecture of Catastrophic Change" (Title: "Know Escape") |

Performers on recording: Actor — Robert Keefe Tenor — Aurelio Viscarra Zulu Spear — (South

African chorus) Gideon Bandile, Babtunde Garaya, Matthew Lacques, Jerome

Leonard, Sechaba Mokoena, Matome Somo, Dumile Vokwana Savina — (Eastern

European chorus) Susan Volkan, Sunita Vatuk, Janeen Wyatt The San Francisco Chamber Singers — Christine Callan, Robert Fink, Robin Hale, Loretta Janca, Cheryl Keller, Charles Lynch, Michael Mello, Jim Murman, Peter Stein, Alain Stora, Karen Tesitor For more music from this production, click HERE |