THE SANDGLASS : A JOURNEY INTO THE UNDERWORLD

by Steve Mobia

BOOKS | SLEEP DREAMS & DEATH | TIME | SEX | NARRATIVE STRUCTURE | OTHER FILMS

Wojciech Has's "The Sandglass" (also known as "The Hour-Glass Sanatorium") is a web-like film, spinning together strands from a dozen stories by Bruno Schulz into a haunting transcendental vision exploring the process of decay as it relates to memory and culture.

Bruno Schulz was a Polish Jew who only completed two books of short stories during his lifetime. Being very reclusive, it was only after prodding by a famous novelist, Zofia Nalkowska, that his first book, "The Street of Crocodiles" (aka: "Cinnamon Shops") was published (in 1934). This was followed by a slightly longer book, "Santorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass," in 1937. All the stories in these books are written in first person narration and most are about the same characters. Also, most are not "stories" in the specific sense of a linear narrative, but more like fantastic, sensual descriptions – mixing the commonplace with the magical. They are generally considered autobiographical but it is hard to tell where straight autobiography ends and the completely imaginative begins. The Polish city of Drogobych in which Schulz lived and wrote about was a Jewish provincial village, steeped in traditions of which he apparently felt both excluded and mystified by.

|

Self protrait of Bruno Schulz |

|---|

Schulz's father was a bookkeeper and cloth merchant who was completely caught up in running his shop with grave seriousness but who also had a wild eccentric philosophical side, which Schulz explores thoroughly in his stories. Aside from the two books, and a few salvaged letters, Schulz's writings did not survive the turmoil of the Second World War. The Nazi genocide and utter annihilation of the Jewish culture in Poland had grave consequences for many and Schulz and his work were among them. He did love to draw and made his living teaching drawing at a local high school. His characteristic drawings were also used as illustrations of the texts. He was later working on an ambitious novel entitled "The Messiah" but that work also appears to have been lost. In November 1942, a Nazi shot Bruno Schulz dead in the street.

Wojeciech Has, a director who was drawn to adapting literary work and who had completed a previous synthesis of short tales with "The Saragossa Manuscript," decided to take on the seemingly impossible task of translating Schulz's literary poetic style into a visual equivalent. Much of Schulz's power comes from the way his descriptions are written – the rich sensual language that is at times so dense one has to digest it slowly. Consider how you might film the following: "Fall is a great touring show, poetically deceptive, an enormous purple-skinned onion disclosing ever new panoramas under each of its skins. No center can be reached. Behind each wing that is moved and stored away, new and radiant scenes open up, true and alive for a moment, until you realize that they are made of cardboard. All perspectives are painted, and only the smell is authentic, the smell of wilting scenery or theatrical dressing rooms, a pile up of discarded costumes among which you wade endlessly as if through yellow fallen leaves." (from "A Second Fall")

Compared to these extravagances of language, the film appears much humbler. Striking transformations from the written texts (such as the father changing into a large horsefly or a small parcel into a gigantic camera-bellows automobile) are excluded from the film and it's hard to imagine actually filming those scenes in the early 1970s without resorting to animation or awkward special effects which would have been noticeably different from the style of the rest of the movie. It's possible now with computer graphics but not back then.

Wojciech Has ultimately created a consistent texture of events which, although less fantastical than the stories, still catches the essence of the Schulz personality and suggests vistas beyond the observable.

The stories are freely adapted and sometimes drastically altered. Also, Has at times inserts his own images and statements which are not to be found among the short stories but compliment or extend a situation (the recurring appearance of the train conductor or the severed head of a female Holofernes are examples). Most of the dialogue can be found in the stories though often spoken by different characters in different situations.

What unifies this abundance of material is in large part the film's visual style. There are many tracking camera shots, some very long and intricately choreographed. The sets were built dovetailing into each other, providing a smooth continuity of movement, which hides for a moment the realization of location change and blurs the distinction of a fixed place. The overall effect is similar to remembering a dream in which you aren't sure exactly how you got from A to B, you just know there was a change. Unity is also achieved by using a single central actor as the main focus – the first person narrator of the Schulz stories. Even in childhood scenes Joseph stays the same age though his childhood friend, Rudolph, is a young boy. The references other people make to him about his age often don't refer to his present physical appearance. This disjunction, because it is used consistently, helps unify the episodes and illuminates a sense that even as an adult we are living all our pasts out simultaneously – that the child is alive within the adult.

Though the material comprising "The Sandglass" comes from a dozen stories, there are two stories that provide the bulk of the content: "Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass" and "Spring." The "Sanatorium" story provides the setting and situation into which the rest of the action is nested. "Spring" provides material relating to Joseph's childhood (the episodes involving Rudolph, the stamp album, Bianca and the waxworks figures). In "Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass" as well as in the film, Joseph rides on a strange train to visit his dying father in a sanatorium where time is altered. He is met by a doctor and informed about the unpredictable nature of things there. Joseph then experiences a profound series of disorienting events in the local town, resulting in the realization of his father's death and his eventual departure to live on the train as a "railwayman." The ending in the film is more ambiguous: Joseph realizes his father's death ("It's a good thing father's dead, and all this doesn't affect him") and crawls out of an open grave, but walks back toward the entrance of the sanatorium. He has been dressed as a train conductor but there is no sign of the train.

Though it is tempting to describe the fascinating selections, omission and alterations from Schulz's original stories as will be discussed briefly later, it seems best now to concentrate on the film presentation itself, of how events in the film do not refer to the written stories but exist by themselves as a separate cinematic experience.

In "The Sandglass" there are major thematic repetitions of subject and image that upon each appearance add more insight into the symbolic workings of the whole.

BOOKS

There are many references in the film to texts and books – specifically two books; a strange advertisement catalogue worshiped by Joseph as part of the "Authentic Book" and the stamp album owned by Rudolph ("the Universal Book"). From the page of these volumes, Joseph attains information and develops concern over the events surrounding him and it is the texts that inspire youthful enthusiasm and action. Ironically, it is also the texts that lead him into self-doubt ("I misunderstood the scanty traces and indications of the stamp album and wove them into a fabric of my own design," he says before nearly killing himself.)

The Biblical Joseph was a dream interpreter and reader of prophecies. Joseph of "The Sandglass" strains to interpret the world and see universal truth in his personal experience. In this quest he is constantly frustrated yet also encouraged by the prophetic characters he meets. He takes his philosophical task much more seriously than his father who announces, "The book is a myth we believe in when we're young but later see as a joke." Adela wraps Jacob's lunch with pages from the "Authentic Book." She laughs when Joseph crawls around her room gathering up the lost pages. Later in a jungle bedroom, Bianca confesses her resentment toward Joseph's "sense of mission."

Joseph twice discusses the nature of books with his father. In the first conversation, Jacob exhorts to read between the lines where flocks of swallows fly. In the second, he advises paradoxically to not be distracted by the cries of birds with their faulty punctuation.

From these observations, it can be said that Joseph is seeking a transcendent knowledge. He is desperate in his search for meaning and looks for signs and assurances in a constantly metamorphosing and degenerating environment.

There is a fascinating relationship developed between Joseph and Rudolph, the young boy who owns the stamp album. Rudolph is cynical, practical and appears to have little patience for Joseph's flights of imagination. Though Rudolph is a stamp collector and faithful keeper of the album, he has no insight into the deeper secrets the album may contain. To Joseph, the album is full of portents and untold stories, all of them true and certain. After seeing the young girl, Bianca, through the gate of her villa, he begins to interpret the album in a way which makes Bianca a kidnapped princess. Rudolph, of course, dismisses Joseph's story. The irony here is that even though Joseph is infatuated with Bianca and is weaving a fiction that makes him into a hero, it is Rudolph who eventually is seen with Bianca in the coach. She had chosen Rudolph instead.

Joseph is seen as an outsider. When at the peak of self-importance, when he has mobilized an army of mechanical wax figures, he discovers that the unassuming Rudolph has been selected by the object of his obsession, Bianca. Earlier when Jews are singing their praise to the Lord, Joseph is unable to join in – either forgetting the phrases or finding it awkward to sing. When at a village feast he is served a large plate of fish, he discovers the fish has already been eaten before he had a chance to have a bite. His father Jacob is in center stage, the grand patriarch next to whom he feels powerless and ignorant. Though old and dying, Jacob is still full of life – feeding his pet birds, declaiming in the public square, continuing to run his textile shop even when his fabrics are decaying. Jacob is seen as a prophet and teacher, larger than life.

That brings us to one last book, the decal book that Jacob presents to Joseph. Joseph transfers a bird of paradise to its page and automatically makes bird-calls. At this point, Joseph incorporates Jacob's passion. Even here though, Jacob is the one who teaches for he names the sounds issuing spontaneously from Joseph's mouth.

SLEEP, DREAMS AND DEATH

Aside from the repeating references to books, bedrooms play an important role in the movie. There is the train in which people are either dead or asleep; there is Jacob's bedroom in the sanatorium with the doctor advising Joseph to lie down; there are hammocks in Jacob's shop in which the shop assistants sleep; there's Adela's bedroom and bed, under which Joseph crawls; there's Bianca's jungle bedroom and Jacob's attic bedroom. All these evoke sleep, dreams and death.

Sleep, as we know, is a state very similar in appearance to death. During R.E.M. (Rapid Eye Movement) periods in sleep, our body muscle tone drops and we are, in a sense, paralyzed. During this period we experience intense inner visions, often centering around major conflicts and non-chronological events from our waking experience in symbolic form. These are dreams of course, and the imagery, dialogue and shooting style of "The Sandglass" very much corresponds to what we know about the experience of dreaming. Even so, it is more like a semi-lucid dream. A lucid dream is one where we are fully aware that we are dreaming. At the point of this awareness, we can assert some active conscious power over the events of the dream. A semi-lucid dream (which is a term of my own), is one with many overt references to dreaming but not direct discovery that one is dreaming.

In "The Sandglass" there are many obvious references to sleep and dreams. The chambermaid in the sanatorium says, "Here everyone is always asleep." The shop assistants refer to the biblical dream of Jacob's ladder. Adela mentions the sleep of firemen hanging in the chimney like cocoons. Joseph is arrested for having a dream that was criticized in high places. Bianca says her mother has to share her sleep with phantoms. When Joseph's mother takes Joseph to the attic, she speaks an eloquent eulogy to Jacob while birds are seen dying and being eaten by insects. The eulogy clearly refers to dreams: "He was one of those whom God touches in their sleep so they know what they know not and are filled with uncertainty, while reflections of distant worlds pass over their closed eyelids."

Though one can have a dream that is so obviously a dream but the dreamer remains unaware, Joseph in "The Sandglass" is so caught up in the wondrous machinations of his memory and imagination that he fails to see his own predicament. A foreboding emissary is the blind train conductor who haunts the proceedings like a death figure. The train is only shown in the opening scene with dilapidated carriages full of apparently lifeless people. The train appears to be a shuttle for dead or dying souls. Just as Jacob continues to sell his fabrics, unaware of their obvious rot, Joseph continues to believe it is his father's death he's witnessing, not his own. As the film progresses, Joseph begins to loose his own eyesight, while the already decomposing world around him accelerates in decay. As Joseph loses his sight, objects in the sanatorium become increasingly closed, nailed up like coffins, and ready to be sent away. The progression of Joseph's journey is toward a resolution concerning his father's death and ultimately his own mortality while his cherished memories flash brightly for one last time before his vision extinguishes.

|

The watch peddler |

|---|

TIME

The film's title naturally refers to time and there are many references to time in the film. The Polish word for hourglass, "klepsydra," has a duel meaning – indicating both the hourglass device itself and an obituary notice. From its creation in the eighth century, the hourglass has come to stand for mortality, aging and death.

Strangely enough however, there is no hourglass to be seen in the film. The only oblique reference to it occurs in Jacob's bird attic. While he's busy building nests, he talks about disengaging the grain of time as he sprinkles birdseed down. The sand grains of the hourglass are compared to birdseed, thus death to regeneration.

There are many clocks and watches in the film however. Unlike an hourglass that pours in one direction until the glass is empty, a clock creates a sense of eternity as the hands round the circle to begin their journey again. There might be no external evidence of a clock stopping until the hands cease to move. This hidden fate is conveyed in Joseph's uncertainty until the end as to whether his father is alive, dead or dying.

Before going out to his new shop, Jacob holds up a watch, which isn't working and says he overwound it. Jacob's sense of duty compelled him to try and store up too much future time by overwinding his watch. He was rebelling against his own old age.

The very first image of humans in the film is accompanied by the image of a clock. As the camera pulls back from a view of a black bird and entwined branches to reveal the interior of a train, we see that among the passengers there sits a rather large clock.

Probably the most vivid clock image is when the watch peddler appears – he wears a board covered with dangling watches. The peddler is fatalistic about the lives of men, saying the rich will die rich and the poor will remain so. In other words, time does not change the basic material circumstances of one's existence. This comes across as a defeated resignation since the peddler appears as a lonely destitute man who refuses to join in the feast.

The two conversations Joseph has with the train conductor suggest that there is a limitation to time – only so much can happen: "There are things which cannot fully happen. They are too great to fit into any one event, and too marvelous – they are only trying to happen." Even so, the conductor confides that there are illegal side branches to the main progression of time, where some of these marvelous events may take place.

Rolls of fabric become a very striking visual symbol for the progress of time. Jacob is a textile merchant and his shop is full of colored fabrics. This compares to the Biblical story of Jacob giving Joseph a "coat of many colors." The metaphoric connection between fabric and time is made clear at the end of the film in a conversation Joseph has with the doctor where he doubts the value of turning back time: "Does one get time at its full value, a true time, time cut off from a fresh bolt of cloth, smelling of newness and dye? On the contrary, it is used up time, worn and tattered by humanity."

In one scene, bolts of cloth are unrolled in all directions by Jacob's customers. Amid the wild clamor of haggling voices, Joseph floats and bobs like a ship on the stormy sea of colored cloth. He appears lost and sleepy in attempting to deal with non-chronological, multiple layers of time. His only way out is to unroll a giant roll of cloth in one direction, which becomes a red carpet for the three wealthy travelers later identified as "Christian Seipel and Sons," owners of spinning and weaving mills. Joseph's conversation with them involves a debate over cash and credit. Cash represents present time, immediately tangible occurrences while credit evokes the future. The three affirm that cash is the better choice of the two. Joseph's mother complains that Jacob has trouble keeping the shop running because customers buy on credit -- yet, ironically, when Jacob gets another shop he complains that it was difficult to get enough credit to start the shop. At this point Jacob has no future.

Finally, Dr. Gotard refers to time as being a trickster and something that must be carefully disciplined. Joseph's upset is said to be due to the disintegration of time. This relates to the difference between so-called objective time and subjective time. Objective time is that given by the conscious rational world. Subjective time is a flexible experience that may be long or short depending on what is happening during its passage. Memory uses time in a different way. Events are grouped together by association, chronology has little to do with it; we may remember an event that occurred 20 years before clearer than one happening a week ago. Dreams further obliterate chronological time by freely mixing present and past events, uniting them through association and ongoing emotional patterns rather than by dates of occurrence.

|

Adela, the town's sex goddess |

|---|

SEX

A film dealing with the basic subjects of existence would naturally include sexual material and this is certainly true of "The Sandglass." Though there are no explicit sex scenes, there is an interesting array of allusions and dream-like displacements that have distinctly sexual overtones.

The first encounter with sex is when Joseph meets the sanatorium chambermaid who rushes out of a hallway door, her uniform unbuttoned, having just eluded someone's advances. After seeing Joseph, the maid tries to regain her composure and sends him to wait in the restaurant until the doctor is available. This scene makes an interesting comparison to the film's conclusion, which begins with the chambermaid and doctor hurriedly getting dressed after a presumed sexual coupling, strongly suggesting that it was the doctor himself that the maid was involved with earlier. The condition of death and decay in which the sanatorium exists produces this compulsive yet hidden sexual union, since the sex drive is closely linked with mortality.

If all the characters are seen as projections of Joseph's unconscious, then the doctor and the maid express a healing power of sex that Joseph does not openly admit to. He consistently avoids sexual interaction to pursue "higher affairs of state."

The most explicitly sexual encounter is when Joseph climbs a ladder, said to refer to the Biblical dream of Jacob's ladder. Instead of leading to heaven, the ladder leads to the upstairs bedroom of Adela, the local sex goddess (making a satirical comment about what many men idealize as paradise). Adela pulls Joseph into her room, saying that he must have lost his way by taking a short cut to school. By referring to Joseph as a little lost boy, the scene suggests that it was Adela who first excited Joseph sexually when he was young. This is further amplified as Joseph voyeuristically watches Adela undress through a crack in a folding screen. One gets the feeling that Joseph is duplicating an action done when he was a child. Their conversation is an incredible string of sexual innuendos concerning the desire of the local firemen to drink her sweet raspberry juice. She finds the firemen repulsive but Joseph defends them and even puts on a fireman's helmet with a phallic spire on top. Adela is close and affectionate, remarking that Joseph seems different now that he wears the helmet. It's a common boyhood fantasy to want to become a fireman or some adventurous authority figure when grown up. This ties in with the supposed virility of heroism and is carried out further in the stamp album fiction he weaves around Bianca, where he makes himself into a hero.

Realizing that the stories of miracle cures Adela has been reading come out of an old book once treasured by him as sacred, the sexual spell is broken and Joseph frantically tries to find the lost page (appropriately one page is titled "Sexual Neurosis").

Bianca is Joseph's child love, an enigmatic dark-haired girl living behind a white wall who whispers about her dead mother and tells the story of a traveler wondering through the sky comforting a child. Bianca's mysterious nature makes her a perfect target for Joseph's fertile imagination sparked by pictures in Rudolph's stamp album. He creates an entire character background for Bianca that he dictates to her stepfather, M.de V. (who later proves to be artificial himself).

Bianca tells Joseph she wishes to commit treason and to erase herself from her own memory. She seems to be playing along with Joseph's intricate subplots that tie her existence to the rebellious tendencies of Archduke Maximilian, one of the waxworks figures. Perhaps Bianca does not really exist in Joseph's conscious life but here she is cleverly trying to break out of Joseph's imposed plotline by suggesting treason. She expresses her ecstatic wish to become defiled and black in order to renew herself. The sex act can be thought of as a sacrifice and rebirth as the Ego submits to pure impulse. But Joseph's intricately arranged fantasies will not be undone in having a spontaneous romp with his dream-girl. She is too precious to be approached directly. Even though he desires Bianca, his sense of heroism demands that she be put into a context as extravagant as his passion for her in order to justify his presence there. She, feeling unsatisfied with his displaced affection, calls him a coward as he crawls away under a piece of furniture.

It is only later that Joseph realizes the mistake he made with Bianca. After his fish dinner (seductively served by Adela) disappears before he has a chance to eat, he meets Rudolph under the table and repudiates the practical world, stating that his own inner thoughts are the most true. However when he goes to fetch Bianca, he finds someone has betrayed him, has signaled his arrival in advance and that Bianca has left her villa. In heroic haste, he summons an army of wax figures to life with magic words and the names of cities from the stamp album. Joseph is reinforcing his own importance by tying his actions to historical heroes. This is shown to be a case of trying too hard for as the coach is stopped and opened, we see it is Rudolph who has won Bianca's favor and Joseph nearly commits suicide. The attempted suicide is foreshadowed when Bianca's wax robot father shoots himself and Rudolph takes his place, becoming both lover and father for Bianca. Aside from references to Joseph's own father which have mainly to do with the burden of guilt, this episode expresses Joseph's misguided sexual impulse, how he easily gets lost in self deception and is all to willing to punish himself. The peculiar quick surrender of his plans following the discovery of Rudolph in the coach suggest that Joseph already knew he would be fooled and had been plotting his own "abdication" complete with maximum punishment, suicide. This coincides with a question he asks earlier, "Can anything completely new ever happen to us?"

NARRATIVE STRUCTURE

As stated before, the film draws on a dozen Bruno Schulz stories but is most heavily based on two – "Spring" and "Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass." Of the two, "Sanatorium" provides the framing story – the father dying in the sanatorium – while "Spring" provides episodes dealing with the stamp album, childhood passions and the character of Rudolph.

Wojciech Has splits these two stories early on in an effectively unsettling sequence. When Joseph first walks up the sanatorium steps, he finds that the front door leads to a wall of earth and rubble (evoking the conclusion of the movie where Joseph leaves the sanatorium by crawling out of the ground). Finding his path blocked, he makes his entrance through a side window. After meeting with the doctor he hears a dog howl from outside. Looking out the window, he sees himself re-entering the sanatorium grounds, climbing the steps and approaching the front door. Rudolph, the boy, opens the door from the other side and Joseph enters. The blockage has disappeared and the entrance seems to lead to a garden or forest. Wojciech Has has visually set up a context for two simultaneous stories – one happening with Joseph and his father in the sanatorium and the other with Joseph following Rudolph into a world of nature.

The next sequence in the film could belong to both stories (actually it's from the story "Cockroaches"). We see Joseph's face being diffracted and broken up by what looks like greenhouse windows. Large leafed plants lead to a drawing room which suggests Joseph's childhood home and he has a conversation with his mother after he uncovers her like a piece of old furniture. The elements of contact with relatives resemble the "Sanatorium" story while the mother's refusal to see Joseph as an adult suggest the childhood sequences in "Spring."

Again, one can get carried away by comparison between the written stories and the film. With or without reference to the stories though, the multiple entrances Joseph makes to the sanatorium does create a strong duality of narrative line which is made ambiguous by the following sequence with Joseph's mother. The diffracted image of Joseph through the windows at the beginning of the scene as well as his own dazed expression provide a visual metaphor for the state of narrative fragmentation which has just preceded it. We don't know which of the two Josephs we are following or if the mother is in a room in the sanatorium. This scene is also the first time Joseph makes a break from being a stand-in for the "naïve viewer."

What this means is that the viewer at the film's beginning is given little information about where and what things are. Joseph, the rider on the train is a stand-in for the viewer. We follow him as he enters the sanatorium and talks with the doctor. The doctor informs us as well as Joseph of the condition of time there. Joseph's own bafflement and curiosity is similar to the viewer's. So far, we have seen Joseph in a rather passive role, much like the viewer.

The exchange between Joseph and his mother introduces references that only Joseph knows and that the viewer hasn't seen or been told before. He inquisitions her concerning lies being spread about his father. We aren't told what these lies might be. Her comment about Jacob being a traveling salesman coming home late and leaving early, suggest that we are watching an encounter in Joseph's home before his departure to the sanatorium; the lies discussed here possibly being conflicting stories of where his father has gone, leading Joseph to eventually discover the truth, that Jacob has been sent away to the sanatorium. In any case, at this point, Joseph asserts an active personality separate from the viewer's.

One of the unique narrative tactics of this film is how flashbacks are introduced. There is no visible or startling cut to a flashback. Joseph smoothly moves from scene to scene, wearing the same clothes and in apparently "real" time, yet the scenes themselves and the characters in them suggest flashbacks – scenes from Joseph's past. And so we have this encounter with Joseph's mother who sees Joseph as a disobedient schoolboy though he himself asserts that he is not a little boy anymore (though it can be said that little boys constantly make assertions like this and so he is in keeping with the flashback character of himself as a child). The scenes with Adela certainly evoke the past as does his encounter with Rudolph, but these episodes are always presented in present tense, so the flashback nature of these must be deduced from other clues. Though Joseph's outward appearance does not change, his manner of acting does and his facial expression of playfulness, fear or innocent alertness and surprise strongly create the impression of vigorous childhood perceptions. His adult caring role is contrasted with this and acted with solemn concern.

The duality of childhood spontaneity and adult melancholy is strongly felt in a seamless transition at the end of the marriage between Rudolph and Bianca. An officer who arrests Joseph for having "the standard dream of the Biblical Joseph" stops Joseph from shooting himself. He laughs as he is blindfolded and he walks in a state of wild incredulous hysteria between rows of soldiers toward his mother. He cannot see his mother but they touch hand and, as the soldiers file past, Joseph pulls off his blindfold to see that he is now back in his childhood home. The cutting is incredibly seamless and the transition from riverside to dining room occurs without any sudden lighting change or break in actor movement, yet there is a strong change in Joseph. His mother again states she has a headache and Joseph is somber, concerned and comforting – a striking contrast to his frenetic laughter of the previous scene.

Along with flashbacks, there are also many foreshadowing and premonition scenes mostly concerning Jacob's eventual death and Joseph's loss of eyesight. As has been put forward earlier, "The Sandglass" can be seen as a depiction of the period between literal physical death and one's psychic acceptance of the death. On one level then, Joseph knows his father is dead but has not thoroughly resolved his feelings. And so, the references to Jacob's death are realizations that finally culminate in a scene where he actually sees Jacob die.

The foreshadowings are not revealed as complete scenes but as details within scenes. The signs of Jacob and possibly Joseph's death are very widespread throughout – from the large black bird at the film's opening through the décor of the sanatorium and on to later images that accumulate and intensify the process of decay. After the birds die in the attic, the emphasis on death becomes more pronounced; the lack of water in the hallway faucet, the grave being dug, Jacob's shop being nailed shut, the rotting cloth. Though Jacob himself is seen physically alive, the signs of his actual death are many.

Joseph's loss of vision is prefigured by an encounter with the train conductor (who is always depicted as blind) on a chair being carried by war-torn soldiers. Later, in meeting his mother after the marriage of Bianca and Rudolph, Joseph squints out a window, seems hurt by the light and sits down on a similar chair. His hand movements and blank gaze evoke that of the train conductor. When his mother leads him up the stairs to the attic, he fumbles his way, using his hands to guide him. The suitcases and boxes packed near the stairs foreshadow the numbered and packed crates of the last scene in the sanatorium.

Curiously Joseph attempts to strengthen his vision earlier by picking up an extra pair of eyeballs while crawling under furniture. Then, when talking with Rudolph under the table, Joseph covers his own eyes with the previously picked up pair, pretending to disguise his identity from Rudolph: "In whose mind could such a thought have been born?" Later when Joseph seeks out his father's new shop, it is found next door to an optician whose sign boldly displays a pair of bespectacled eyes (an attempt to strengthen vision).

And so in "The Sandglass" we are confronted with an integration of past, present and future events without the usual distinct separations. Everything about the film's design contributes to a sense of continuity even though the scenes are not chronological and don't follow the constraints of standard storytelling.

The beginning of this essay referred to the film as exploring the process of decay as it relates to memory and culture. Bruno Schulz wrote from inside the culture of a pre-World War Two Jewish city in Poland. Wojciech Has made his film looking back at that culture which was totally destroyed during the war. The film has a historical and cultural perspective that the stories don't explore. The Holocaust has a macabre and harrowing influence on even the most ebullient of scenes.

Much of the language spoken in the street scenes is not Polish but Yiddish, giving depth to its portrait of Jewish society. Hasidism, an 18th century mystical-revival movement, which began in the Ukraine, then spread to Poland, pervades village life as shown in the film. The movement stressed religious fervor, prayer, singing and dancing as opposed to strictly intellectual study. A scene early one with the shop assistants joining in song exemplifies the Hasidic spirit.

Jews had been in Poland for over a thousand years and had grown rather insular. The family and particularly a patriarchal structure was all encompassing and bound the Jews together. The term "family" can be applied both to an individual group of relatives and to the Jewish people as a whole who see themselves as family descendants of the three founding fathers; Abraham, Isaac and Jacob.

"The Sandglass" is a film not only of a father's death and a son's remorse but of the death of a culture. Jacob's textile shop opens onto a large synagogue and becomes the hub of the town's social activity. Mourners holding candles pray before what feels like a final feast, the last gathering before the great scattering that would take place as the Jews either emigrated or were murdered by Nazis.

The fabric of the film blurs distinctions between the personal and the social. There is the nightmarish scene where Joseph watches his father and customers haggle over a piece of decaying cloth. Joseph goes into a back room looking for a letter sent to him. He ends up in a moldy tomb-like chamber. Looking back, he discovers his father and customers are no longer in the shop. The next moment, shouts of people can be heard and through a grating on a high window can be seen the town's population running in panic, carrying their belongings – a fearful exodus greatly suggesting a pogrom. Shortly afterward, Joseph finds his father in the sanatorium and watches as he dies. There is here a union of inner and outer worlds, the specific and the general, an individual's life and a collective life.

© 1983 Steve Mobia

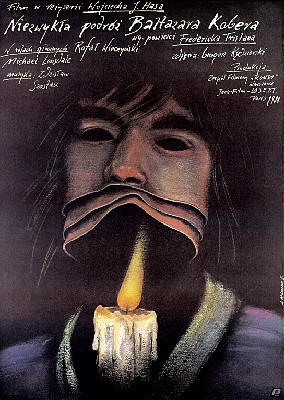

"The Tribulations of Balthazar Kober" movie poster

OTHER FILMS BY WOJCIECH J. HAS

Wojciech J. Has died in October 2000, leaving behind a body of unique films. Most are intelligent and personal adaptations of literature. His most well known production is "The Saragossa Manuscript" (1965) based on Jan Potocki's novel that has a Chinese box structure of nested stories.

Other Wojciech Has films that might appeal to those who appreciate "The Sandglass" are:

"Memoirs of a Sinner" (1986) An exhumed corpse tells a story of fighting his evil alter ego. It has the fine visual detail we would expect but gets bogged down in the lengthy and wordy center section concerned with moral issues of good and evil. Still, the later scenes are worth waiting for.

"The Doll"(1968) is a strange portrait of a failed courtship as a man tries to woo an unresponsive aristocratic woman. Based on the novel by Boleslaw Prus.

"The Tribulations of Balthazar Kober" (1988) is set in a metaphysical phantom world where everyone discusses theology. Balthazar, escaping the seminary and the 16th century German inquisition, searches for spiritual truth. There are many remarkable visionary images and an oddly detached sense of humor.

Other Has films of interest include "The Codes" (1966) in which a father searches for his son after WW11 and "Write and Fight" (1985) which concerns an imprisoned writer's feverish delirium.

The soberly titled "A Boring Story" or sometimes "An Uneventful Story" (1982) is based on Chekhov's tale about an aging professor's disillusion with life.

Hopefully these fine films and more will someday be publicly available for all to see. Wojciech Has deserves a place among the very best of world cinema artists.

© 2006 Steve Mobia (from an essay written in 1983)

Reference:

Jerzy Ficowski: Regions of The Great Heresy (Bruno Schulz, A Biographical Portrait). Published by W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.