|

|

A positive attribute of symbolic films is their openness to interpretation and so I hesitate to give such an explicit meaning to this movie. By delving into ones personal meaning and association, the viewer meets a symbolic film halfway and it attains a personal dimension that a more literal narrative structure wouldn't have. The script for Limboid took over 4 years to gestate and had taken a few forms before the final version solidified in 1981. One result of this long rumination is that the symbols picked up many layers and the final result is probably "overdetermined" and has led many viewers to be baffled as to my intent. This was not a desire to subvert interpretation or merely present a puzzling string of "surrealist" images but that complexity of the structure needed multivalent symbolic images to most honestly express the content. Unlike classical Surrealism, the images in Limboid are all very intentional as to their meaning and to how the overall structure is constructed. However (and this is a big thing to me), I did not want to limit the viewer's imagination. It's also surely true that I wasn't aware of everything I had put into the film due to my own mental "blinders" and limited perception. If knowing what I had in mind might ruin the film for you, I suggest you don't read this text!

|

|

An "arrowhead" symbol is used in it's inverted form during the "Battlefield" section where it represents rage and pain |

The symbol is shown in the "Hedging" section as a transcendant form |

OVERVIEW:

Ashla, the woman painter in the film represents the creative urge and the changing of her painting style reflects a different attitude toward this urge and a different channel for expression.

She undergoes 4 style transformations in the story.

1. Action painting (Battlefield): The enemy is the void (blank canvas) and by implication non existence. The emotional struggles are in evidence around her: her indifferent parents, the inner art critic, the punished young girl. Creativity is a self conscious struggle.

2. Geometric: This stage starts the "Hedging" section of the film. Geometric shapes proliferate in Ashla's studio and she uses them to set her hair. Creativity is appreciation of form

3. Representational: In a complete reversal, her new painting appears photographic and lifelike -- so much so that it actually incarnates her inspiration -- a romanticized yet cold version of the feminine. Creativity is communication through commonly understood references.

4. Reflective / personal. The old woman drops stones in a pond. She does this privately with no expectation of fame or appreciation. In fact, she realizes that most would not even notice her careful placing of stones in the pond and would just think the stones just happened to be there unintentionally. Creativity serves a personal need, regardless of recognition.

—————————————————————————————————

A TOUR FROM BEGINNING TO END

LIMBOID (title conflates "limbo" and "void" as well as the word "limb" which is a recurring image. I was thinking a Limboid was a person or entity that exists in limbo)

PRELUDE:

The opening we see a very low angle tracking shot of a trimmed hedge, looking up into the sky. The camera here was mounted on a skate board and rolled along a smooth track. We hear a mother instructing her daughter on the importance of keeping the hedge trimmed. The hedge dissolves away and we see Ashla, the painter, as a rooted tree on a hillside with branches growing from her shoulders.

A hedge and then a series of flowers are cut with hedge clippers. Finally we see a group of girls dressed as surgeons cutting everything in sight with their hedge clippers. They've taken the mothers advice to an extreme and don't know when to stop.

The prelude sets up the major conflict between wild nature and trimmed domesticity. The artist is identified with growth and "wildness" while the young girls are performing an operation so that "everything looks neat" under instruction of the unseen mom.

|

| Energy from stagnation |

PART ONE: BATTLEFIELD

A classical statue of a putto (baby angels that influence human affairs) holds up a white sphere. The statue is in the middle of a swamp. The sphere explodes, sending shards in all directions. This image works on the idea of stagnation leading to eruption and violent change. The destroyed sphere reassembles twice later in the film. I was reading a lot of Jung during this period and the image of the sphere as well as the Animus figures associated with it are meant of evoke the archetype of the self beyond the ego. The self appears to be destroyed but becomes whole at important points in Ashla's development.

The series of shots of the broken sphere is a landscape that suggests ruined buildings or classical monuments. Also there is blood on the sharp edges, showing that there are earthly life sacrifices at stake.

A robotic looking man and woman (as an old dress form) are among the broken concrete structures. A hat rack protrudes from the rubble and the artist, dressed as a soldier picks out a helmet from the other options, places it on her head and suddenly is possessed with determination. Throughout Limboid, the hats and other items placed on Ahsla's head represent her thought patterns. She leaves the area and is pursued by 2 men wearing suit and tie. One man is dressed in a patterned sport jacket. He is the gallery owner. The other, dressed more straight, is an uneasy business man investor being introduced to the art market. They are later seen watching the creative process from a safe distance. The last image of a wooden sign picturing a clown are meant to clue that this section of the film has satirical intent.

Pausing in her advance, Ashla sees a young girl in a marshy meadow offering a small present wrapped in floral paper. Ashla notices that the girl is walking through mud and indeed her present becomes excrement. This is a complex symbol. The girl is meant to be a double of the blond girl in the second part but of a different quality. This girl is dark haired and is associated with nature and bodily functions. The blond girl later is shown to be looking heavenward and is seen offering her gift before spinning geometric forms. Both offer gifts that Ashla recoils from. The "Happy Birthday" song is connecting with early creativity, the excrement that to a child appears to be born from them. In turning away from girl of mud and excrement, Ashla creates a vacuum that is filled by the executioner (who tellingly has no face and wears a brown robe).

Ashla runs into a POW camp; a corral where the prisoners are blinded by maps. In addition, each prisoner wears a black tie and a white cape. Here I was connecting the notion of Superman (the cape) and Clark Kent (the tie) as one. The map covered people represent the society at large, trapped by definitions (the maps) and each feeling like a nascent super hero while behaving like blind fenced in cattle.

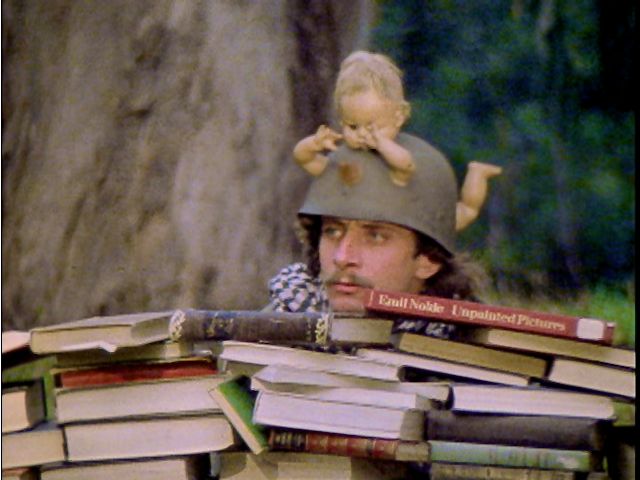

Next, Ashla runs past a fox hole where the sand bags are books protecting an art critic/ war correspondent who wears a helmet with a baby doll protruding. The baby doll hemet (I called it "Infantry") represents the union of defensiveness and vulnerability. When someone is defensive, they feel vulnerable. Art critics are often frustrated artists themselves and so feel vulnerable when commenting on other artists. Much of these comments take on a defensive character, advancing an argument that protects the writer much as the books do in this image.

|

| Mark Knego as the Art Critic / War Correspondant |

Coming to hide behind a large cut tree trunk, Ashla peers at her adversary, a blank canvas. She suddenly feels defeated, having no weapon with which to fight this foe. To her left she sees an image from her past, a carrousel horse sitting on top of the rooted part of the trunk. But her parents stroll in to the picture, disapproving of her situation.

To Ashla's other side a white membranous form appears and of of it, a strange man dressed in a purple loin cloth. Purple is the union of passive and active principles and so the man has both these qualities. He holds a painters palette which he gives to Ashla and pulls a paint brush from his genital area. His character name is "Sunima" which is an anagram spelling of "animus" or Jung's concept of the man inside the woman who gives direction and goals to the more encompassing female spirit. After Ashla takes the brush the man vanishes inside a white sphere that ascends a steep hill. The sphere is of course a reference to the exploding sphere earlier that started the Battlefield section and indicates the self can be changed but not destroyed.

The executioner approaches the nature girl and strips off her clothes. He and his henchmen then fasten her to the back of a large painting labeled "bleeding heart". A photo of a fear stricken Ashla is placed over the girl's own face. She then becomes the suffering, compassionate younger self and an aspect perhaps a guiding force in Ashla's art performance.

Cutting away from this scene is a shot of colored water balloons in a basket being carried to the POW camp by the "Avant Guards." They all wear very different and strange hats (different thoughts) but each has face painted arrows pointing to their eyes, mocking the maphead prisoners who appear to be blind. They proceed to throw the balloons which splatter colors on the prisoner's capes. The guards are then meant to be artists who celebrate their "vision" and use the foibles of mainstream society (the POWs) as a canvas for their work.

The young girl is forced to crawl on her hands and knees while the executioner's henchmen whip a tormented painting of faces that the girl wears like a turtle shell. This punishment of the innocent incites anger and energy in Ashla and she attacks the blank canvas. Her first mark is a sweeping black line which becomes a backbone of the abstract action painting she is creating. The revelation of this effort is too much to bear however and Ashla runs from her creation, This attitude toward art defines the "Battlefield" section of the movie: the artist is both attracted and repelled by her creation. The huge effort in creating the vision is a struggle where other forces (indifference, mashocism, self criticism, the society at large) all have a place. I meant that all the characters in this section are not actual separate people but forces within Ashla, much as dream characters are all parts of ourselves. At this point there is much cross cutting between the various characters while Ashla completes her painting.

.jpg) |

| The "bleeding heart" victimized |

There is dissension among the POWs where one forces another to see by burning a hole in the map with a magnifying glass (Washington DC, is the location of this new eye). The war correspect/art critic's typewriter sounds off like artillery, each word and sentence an attack.

The business man and the gallery owner settle in to watch Ashla's performance intently through binoculars, but Ashla's indifferent parents are bored and cover their open yawns politely with paddles that display a closed mouth.

.jpg) |

| Polite indifference |

Not content with just whipping the tormented painting, the executioner gets an ax and brings it down on the painting himself. Suddenly the others take notice. The parent figures don surgeon masks beneath the polite "Yawn Covers"

From the split painting comes gushes a spring of clear water, the girl's physical body having apparently transmuted into this element.

Ashla drops her brush and collapses from sheer exhaustion. The water from the axed painting now appears to have formed a lake around it.

The business men are happy, the painting meets with their approval. A check is exchanged between the art investor and gallery owner and the two approach the fallen artist. In the most obvious satirical image, the gallery owner gives Ashla a tiny corner of the check — useless to the artist. She awakes in anger as the businessmen approach her painting.

The white sphere reappears, summoned from Ashla's inner outrage. From within, another "animus" character emerges; much older and bearded. He approaches the POW camp holding hedge clippers instead of a paint brush. The Avant Guards are terrified at the thought of the masses being freed and run away.

.jpg) |

|

| Sumina one | Sumina two |

The bearded man snips the rope on the POW corral and his body explodes into a puff of smoke (like the sphere at the beginning). The prisoners suddenly have a direction and run from the enclosure as if magnetized. They run across a steaming landscape (which was actually horse manure giving off methane gas).

The businessmen are startled as the POWs stampede over them to get to the painting. In the center of the painting is the inverted arrowhead form. I meant here that the arrowhead on the stylized back bone would be compared to the executioners ax that fell on both the painting and the girl's back beneath. The POWs pick up the painting and easel and run away with the businessmen in pursuit.

So what does this sequence mean? The POWs represent unrealized potential of the general public. My notion at the time was that the public is caught in a defined world (the maps) and their directionless situation is exploited by the elite artists who mock the public's blindness as material for their art (the paint balloons on the "super hero" capes). When the public becomes energized, it claims the "action painting" as their own — not something to be bought and sequestered in a gallery but instead a vehicle for action itself. The soundtrack here is interesting. I recorded babies in a hospital getting circumcised and then overlapped multiple recordings of the babies screaming. So, symbolically, the Amimus cutting the rope is the cutting of the umbilical cord— the POW's are newly born and have a direction. However, when they grab the painting, the recording slows down, the same baby sounds but now mimicking cattle.

The art critic/war correspondent finishes his review/report and leaves. Ashla's indifferent parents fade away as does the carousel horse link to her childhood. All the forces propelling her struggle vanish and she is left alone. She removes the defensive helmet and tosses it away. She runs past a pile of art books, leaving them behind. One is opened to a Giorgi de Chirico painting of a faceless artist at an easel overburdened by the past (old classical architecture).

This chapter in the artist's life is closed. Art as a public spectacle of struggle and self conscious victimization is left behind.

TRANSFORMATION PASSAGE

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

She descends a steep hill and approaches a lake. Suddenly she is struck with an intense pain in the neck. A lamb skull is seen as if biting the back of her neck. I think of the lamb as symbolizing meekness and is often used in ritual sacrifices. Here meekness and purity brings the self aggrandized artist down to her knees. A great change is afoot.

The hands that touched the skull now begin to molt. Ashla begins to shed her skin like a snake. We see the destroyed painting of torment floating in the water — hopefully signaling to the viewer that the water was created by the sacrificed "nature girl" and that this is the lake produced when the painting was axed. The transformative aspect of this scene is further amplified by seeing an actual snake at Ashla's feet as shed skin is flung into the water.

Ashla sees a vision and kneels to look closer. A idealized blond blue-eyed girl child looks up from the water. Bubbles of air float to the surface. So here the nature girl (mud, excrement) is reincarnated as a pristine blond in a Victorian dress.

PART TWO : HEDGING

The arrowhead painting is the first in a series of abstract paintings that gradually become soft and round, finally ending on an obvious stylized vagina. Over this procession we hear the mother again instructing her daughter about the importance of clipping hedges and the girl makes up a song about it. I intended the abstract forms to represent the notion of clipped hedges — the extraneous "wild" elements circumscribed into basic shapes. Also, like the hedge at the beginning of the film, it is a long tracking shot, perpendicular to the first (vertical, horizontal).

We see Ashla at a make up table, putting geometric "curlers" into her hair. She goes to her bed while massaging her neck (where the lamb skull bit her). While starting to make up her bed, she sees something strange about the pillow and pours brown leaves from within.

I had this notion that our dreams could collect in our pillows and in the morning, we could pour remnants of our dreams from the pillow cases. So here Ashla pours leaves from her pillow, remnants of the dream that follows (the only signaled dream in the movie).

A young girl is stacking rocks to form a little hill while an older woman calls to her. Reluctantly the girl takes apart her hill and places the rocks in a basket.

|

.jpg) |

Back in Ashla's studio, we see she's made a mobile of the leaves from her pillow. She is painting a lifelike representation of the girl seen in the lake. The girl in the painting has her eyes closed, as if dreaming the painter. Ashla adds a dab of paint to the girl's cheek and she's suddenly alive in the room, eyes open. She kneels down and supplicates before the vagina painting that conjures a wind. Flowers are born from the vagina painting and the girl offers this bouquet to Ashla whose face is now smudged with actual ashes. Two important elements here are the spinning geometric forms behind the girl and the religious aspect which is further enriched by the choral music. The flaming flowers echo the gift of the nature girl (the "birthday" present had floral patterned paper). Here fire takes the place of excrement and mud. Again, Ashla rejects the gift; in this case by raising a white gossamer cloth (purity) as protection from the heat of the burning bouquet and covering the girl's face with it.

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

| Rejected Gifts | |

So by painting the girl in such a representational way, she becomes too lifelike and Ashla must shield herself with the white cloth (her idealized projection of innocence). The girl, again asleep, covered in cloth, reclines through a series of dissolves and transforms into sand. But there's not only one face, but many. By reducing her into a elemental nature, she can easily propagate.

Ashla, perched on a rock, extends her arms as if in a performance. She jumps and stamps madly on the various sand faces. The attack becomes ecstatic. Destroying the ideal unleashes passion.

But what is the flip side of this wild abandon? We see the young surgeon girls, roaming the countryside with their hedge clippers. Ashla is here too, as a tree on a distant hill.

Okay, time to pause a bit. The basic conflict in this film is between cynicism and innocence. Not innocence in terms of ignorance but openness and offering- experience becomes truly new . And cynicism here is often shown by Ashla's reactions. Even though she is an artist, her vulnerability to innocence engenders a protective cynicism. I noticed this in many artists at the time. They were creative in certain ways but jaded and judging in others. Also I noticed this opposition in myself. If you create without any judgement, there is a good chance what you make will be puerile. The trick of a successful artist is to be open to the new with fresh eyes but to shape the material with sense of innate structure that comes through practice and experience.

Anyway, back to Lmboid. We see Ashla with leafy branches in her hair (taking the place of the geometric shapes). The branches growing from her body sprout hands with paint brushes that appear to be painting inspirational birds into the sky. One of these birds (an egret) flies over the lake seen earlier where now the young girl and the old woman from Ashla's dream appear. As before we get the sense that Ashla is creating the environment wherein her personal drama unfolds. The young girl in the dream runs away from the old woman, thus setting up the theme of brash youthful independence between them.

|

| Urge to Independance |

What does the young girl see? The surgeons approach the rooted Ashla and they pull one of Ashla's branches earthward. One of the surgeons with blond hair extends her hedge clippers and clamps them around Ashla's "arm."

Back in the studio, Ashla drops her paint brush. Without creativity, Ashla perishes. The other surgeon girls approach. The blond girl removes her mask, revealing that she was the subject of Ashla's inspiration—the idealized feminine who is in a separate pristine reality although here wearing Ashla's purple eyeshadow. Essentially a revenge, Ashla now becomes a sand representation and an erasing wave reduces her even further into the elements. The tables are turned.

.jpg) |

The girl from Ashla's dream runs in panic back to the old woman. Suddenly the old woman looks directly at the camera (breaking the forth wall) and speaks. This scene is a fairly accurate translation of an actual dream where an old woman confided in me about her art. She would gather stones from all along the earth and bring them to her special pond. After careful consideration she would drop her stones into the pool to form designs beneath the water. If any not privy to this knowledge would happen by the pool, they would just think the stones were there by accident and not brought deliberately from around the world. They wouldn't respect the placement and might pick up the stones to throw at birds.

So the old lady was confiding that her art was a private ritual, not the public spectacle of the Battlefield not the hermetic nature of the geometric forms or the melodrama of the representational. She was essentially doing this for herself and the child (who may or may not be related).

The elder lady walks away with an empty basket. The young girl produces a stone that she hid from the old lady. The youthful rebellion/independence theme is carried forward as the girl looks up at a flock of birds in the sky. Her decision both to hide a stone from her elder guardian and also to consider throwing it at a bird transforms the material in her hand. The stone becomes a 3D representation of the arrowhead form. The suggestion here is that independence is essential to transcendence. If she had just followed behind the old lady and never asserted herself, there would be no progress.

|

The shape is seen upturned and illuminated in darkness. A fire ignites within the form. The painting that began the "Hedging" section is again seen but this time with a fire painted inside the arrowhead. Like the purple color, the fire within the solid unmoving shape unites two seeming opposites. Fire is consuming and transformative while the shape is fixed. Fire here is a natural force of great power, hedged within the transcendent structure. The painting is seen to be on a wall over a bed where Ashla and the blond girl are asleep. It's a if they both dreamed the proceedings. But more than this the rivalry between them has reached an equilibrium. The fire from the burning bouquet and Ashla's abstraction have found a place at rest. Leaves float down, covering their bed, indicating the connection to the dream characters of the old lady and the young girl who were first introduced with leaves poured from a pillow case.

|

———————————————————————————————————

Shooting of Limboid

Most of the camerawork was done with an Arriflex S 16mm camera with 3 prime lenses that was loaned to me by Ted Selker. Because the camera was so noisy when running, I couldn't do sync sound (always an expensive proposition back then) and decided to do essentially a silent film with occasional voice overs. I didn't have the money to "work print" all the footage so I shot with Kodak ECO reversal stock so I could look at the footage on an editor and decide what was worth making a work print with. This kept the budget down considerably but also compromised the resulting look as negative gives the filmmaker more latitude than reversal and since so much was shot outdoors in forested areas with many bright and dark zones in the shots, I could've used the additional headroom negative provides. Aside from a couple of instances where an optical printer was used, most of the movie is without special effects except for simple A and B rolling and superimposition. Large silver reflectors rather than lights were used for the outdoor shots to fill in shadow details on the actor's faces.

.jpg) |

Steve Mobia and assistant/actor John Law during the shooting of Limboid's POW stampede |

I also decided to write my own music for this film. My earlier 16mm short "Light Fixture" also had my own score but was more sound effects than music. The other super 8 films mostly had "borrowed" music by contemporary composers I liked. It was only much later (in 1995) that I focused on studying music theory and the resulting more complex concert pieces that followed. So the Limboid score is for the most part simple melodically and rthymically. Still, I like the string theme with its ambiguous tonality that opens both the prelude and the "hedging" section. You may notice I do variations on some of the melodic elements that appear in different contexts. So the martial band music that accompanies the POW sequence becomes wistful piano when Ashla contemplates the nature girl, etc. The 5 beat drum rhythm that underlines Ashla's attack of the blank canvas is based on pinball machine relays. At the time of shooting I owned 3 pinball machines and liked many of the sounds. I thought that Ashla's hitting the canvas with paint was like a game when a target is hit.

The lead actress, Cynthia Moore, was a long time member of the radical theater troupe The Blake Street Hawkeyes. Other members of that group included David Shein, George Coates, John O'Keefe, Bob Ernst and Whoopie Goldberg among others.. Many supporting cast members were friends and members of the San Francisco Suicide Club, an urban adventure group led by visionary Gary Warne.

"Limboid" was featured on KQED television's "Frontal Exposure" show in the mid 1980s, and was run theatrically at San Francisco's Roxie Theater. For many years the film was distributed by Canyon Cinema.

CREDITS:

Written, Directed, Photographed by Steve Mobia

Additional camerawork: Mary Mizzell, Doug Kipping, Joe Murray, Tom Wong

Ashla (the painter): Cynthia Moore

Girl in Painting: Mandy Feusner

Stone Collector: Katherine Holabird

Basket Girl: Erin Flowers

Art Investor: John Tzamos

Gallery Owner: Ralph McNeil

Art Critic: Mark Knego

Father: Cyril Clayton

Mother: Helen Valdez

Girl with present: Lisa Tabachnick

Executioner: Geoffrey Blaisdel

Whippers: Bot and Droid

Sunima (young): Yecia Ben Ari

Sunima (old): Bill Ham

Surgeons: Kira La Flame, Kristin Hass, Ava Sandrock, Connie Hoffman, Mandy Feusner

Avant Guards: Diana Walker, Sharon McGowan, Jim Masica, Stephen Berkman, Catherine Rose Crowther, Laura Caponera

Prisoners Of War: G. Sutton Breiding, Joe Weinstein, Brian Doohan, John Law, Laurel Casaletto, Cynthia Williams, Annie Coulter, Matthew Barton, Sarah Schultz, Paul Alsback, Phil Bewley, Victor Doria, Michael Beck, Jean Fisher, Mark Joplin, Steve Tokar, Robin Clark, Jim Burrill

Music Composed by Steve Mobia

Piano: Vicky Tan, Steve Mobia

Flute: Sandra LaRusso

Violin: Jeanie McKenzie

Cello: Kathy Shew

Bass: Paul Matlock

Trumpets: Mark Hoke, Bill Harvey

Trumbones: Ray Pangelinan, David Malespin

Tuba: Mike Bruninga

Percussion: Allan Biggs, Sam Gulisano, Bob Campbell, Phil Bewley

PAINTINGS

Portrait: Diane Reynolds

Geometrics: Dan McHale

Expressionist: Catherine Rose Crowther

Titles: Scott Kim

Crystal Forms: Stan Isaacs

Production Assistants: John Law, Phoebe Bringle, Dan McHale, Cynthia Williams, Marcy Muray, Michael Schenchuk, David Warren, Joegh Bullock, Scott Kim,Ted Selker, Susan Mailloux, Kandall Katze, Stephen Berkman, Michael Beck, Catherine Rose Crowther

...and all those who gave freely of their time and energy

(back

to Steve Mobia's HOME PAGE)